This profile is based on an introduction written by conference director Andrea Bewick for the 2013 conference.

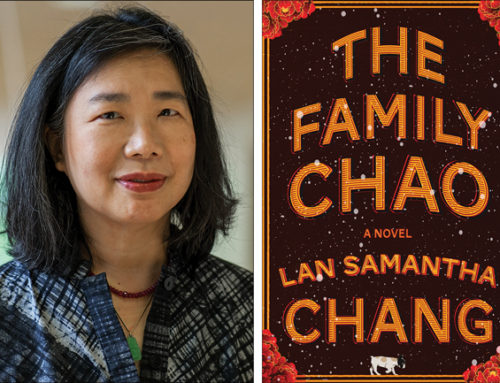

It’s our great pleasure to welcome Lan Samantha Chang back to Napa and the writers’ conference. Sam has been teaching at the conference for many years and, as with many of our beloved faculty who return, we think of her as family. It’s a gift and a grace to be witness to a writer’s life in this way, to share in the birth and growth of new work, to be present for new risks and leaps, and to cheer the well-deserved awards. Sam’s presence here has that particular element to it – that sense of affection and reunion that comes when a dear friend returns. But there is something beyond that, as well. A deep sense of anticipation – of excitement – at once again being in the presence of a writer whose work is marked by profound risk and gentle, shattering insight.

She is the author of the award-winning books Hunger and Inheritance, and the novel All Is Forgotten, Nothing Is Lost. Her debut collection, Hunger, won the Bay Area Book Award for fiction and was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Award. Her fiction has appeared in Atlantic Monthly, Story and Best American Short Stories. She has received fellowships from the Bunting Institute at Radcliffe, Princeton University, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Guggenheim Foundation, and she currently teaches writing at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she serves as Director of the Graduate Program in Creative Writing.

Sam has been described as a writer whose “beautiful, merciless prose” explores the “hungers of the heart: of desire, of ambition; of all we might be, and aren’t; of all we most want, and can’t have.” In All is Forgotten, Nothing is Lost, we are brought into the lives of two men, both poets, who meet in graduate school and pursue increasingly divergent lives. Bernard attends graduate school to find “his One Great Reader.” The one person to whom he will write, whom he will imagine as the ideal witness for his artistic life and work. For Bernard, poetry is an avocation.

For Roman, the novel’s narrator, poetry is more a means to an end. Late in the novel, Roman realizes that what he wanted from graduate school was to find the One Great Judge who would declare him — Roman — the greatest poet of his time.

In the end, both Roman and Bernard are revealed to be essentially similar in their loneliness, the result of having sacrificed every personal relationship for the sake of their work.

For me, the most striking aspect of this novel is its courage. Through her “beautiful, merciless” prose, Sam stares straight into a lovely but terrifying mirror – one that reveals not just our surfaces, but our inner desires, our needs – to examine, head-on, the impulse that pushes us to create, and the lengths to which we’ll go to protect it.

In graduate school, Roman places a small note next to his phone that says, “All that matters is the work.” It’s a phrase that, in the end, haunts every page of the novel, even as it consoles.

In Sam’s work, yearning and its twin — heartbreak — are always intimate — as close as a parent, a lover, a mirror. Settings shift from rural China to New York apartments to Midwestern MFA programs, but what remains constant is the tricky, always foreign terrain of our own hearts. In the short story “San” a young girl watches her gambling father walk out of her life forever, holding a bright, stolen umbrella. As an adult, she accepts that “in mathematics, as in love, the riddles matter most.”

In her work, Sam manages to illuminate these riddles like the geodesists who mapped the continent. Relying, like them, on the humblest of tools — in Sam’s case: words, paper, courage — she shows us the old familiar world, transformed.

A dear friend. A trusted guide. We are so lucky to have her with us again tonight.